“In the great city, there are so many houses, so many families, so many people, that only few can have a garden.”

Such did the famous writer Hans Christian Andersen write in 1844 in The Snow Queen (Snedronningen, chapter two). The “good, kind Danish poet”, as Alexandre Dumas called him, grew up in Odense, where a museum now bears his name, but started his career in Copenhagen.

Un droit de passage pour tous les espaces verts de Copenhague ?

The Danish law prohibits the privatization of access to the sea in Copenhagen. Why couldn’t this apply to all green spaces as well, including the gardens of buildings? Most of Copenhagen’s neighborhoods already meet the principle according to which any accommodation should never be more than a 300 meter walk away from a public green space or the water (Københavns Kommuneplan, 2019) and in the EU, 44% of the urban population meet this criteria (Joint Research Center, European Commission, 2018). Nonetheless, access and use, i.e. the activities allowed in these places, are too often limited, notably due to the private ownership and exploitation of these green spaces. And according to H.C. Andersen, this is not a new statement to make.

Copenhagen’s urbanization, past and present

At the time when H.C. Andersen wrote The Snow Queen (1844), Copenhagen’s urban planning was in the midst of a complete upheaval. 1807’s war and fires had ruined a large number of houses and dwellers had to find new places to live. The city’s fortifications were abolished, and its borders were expanded to new residential neighbourhoods – Nørrebro, Vesterbro and Østerbro (the so called the bro-neighbourhoods). Large bloc buildings were constructed with enclosed spacious courtyards, hidden from the street pedestrians. In contrast, the more affordable city center welcomed the poorer families. On Borgergade, a street along the King’s Gardens (Kongens Have), buildings took on additional floors and gardens on their roofs. By the end of the 19th century, Borgergade was one of the most populated and poorest slums in Copenhagen. H.C. Andersen could have described these neighborhoods in The Snow Queen :

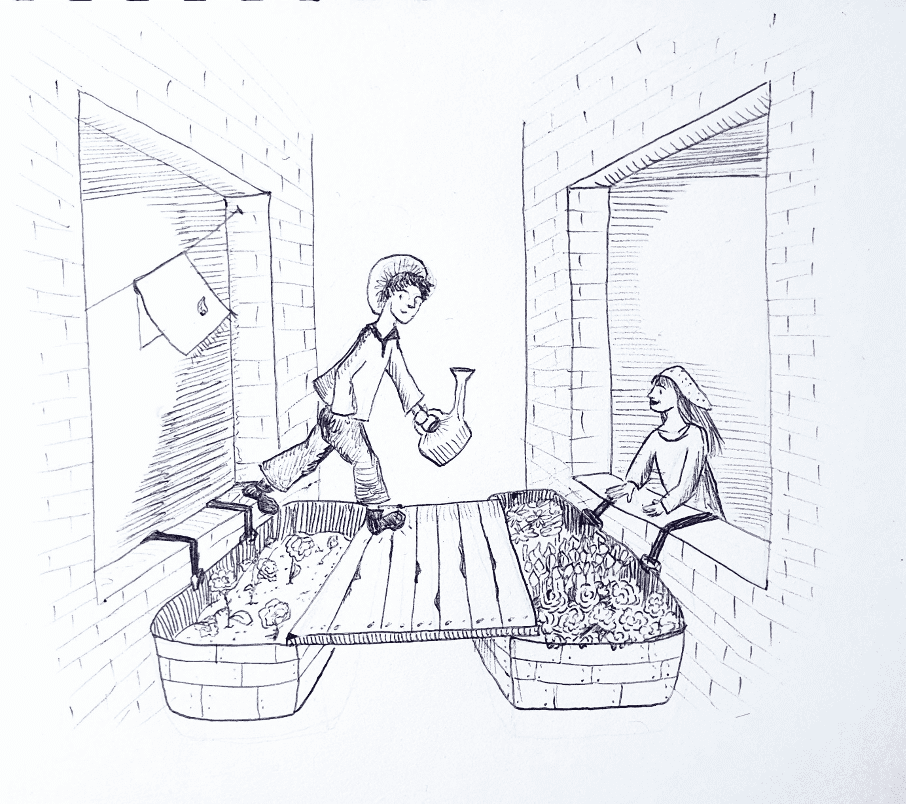

” heir parents were living in a narrow street. They were living in two attics across the street from each other. The roofs of the two houses were almost touching each other: they could safely go from one gutter to the other and visit each other. (…) the parents had the idea of putting boxes across the small alley. (…) The children would come and sit on small benches between the rosebushes. What a pleasure, when they could go and have fun together in their aerial garden! “

Source : Annabelle Moine

Either fully private or fully public

Like in Andersen’s time, access to a courtyard or a garden remains a privilege. The lockdown measures put in place against the Covid-19 pandemic have highlighted the gap in people’s access to green spaces. Since then, more and more Copenhagen dwellers are looking to move outside the city, and thus put even more pressure on the city’s attractivity, which was already a concern for Copenhagen municipality in 2019, as expressed in its vision for 2050 (Kommunalplan, 2019) :

“Copenhageners in all districts – both existing and new – must have easy access to green areas that are attractive to use.”

In fact, what is the point in being 50m away from a green or a blue space if you can’t swim there most of the year or play music after 9pm? Most courtyards and residential gardens are owned by private corporations which, understandingly, restrict their use and access. If their exploitation were made public, then citizens could fairly use theses spaces and therefore, give them more appeal.

Architects’ attempts to emancipate from a dichotomous urban vision

Seen from above, the old bro-neighbourhoods look like a surprisingly green patchwork, with red bricks on the outside and yellow bricks on the inside of courtyards. Bjørn Nørgaard reused this idea to build a sculptural housing building meandering along Bispebjerg Bakke. A housing without a private yard is in itself an architectural provocation against green spaces privatization. Looking like a typical lindworm (half-way creature between a dragon and a snake) from nordic fairytales, Nørgaard’s building snakes around but never closes on itself.

Other architects have been looking for a new compromise, like Vilhem Lauritzen with his realization in Nordhavn: Friksvarteret is a good combination of private and shared spaces, directly accessible from the street (see picture below).

In 2020, the urbanist Gehl is presenting the project “Vesterbro passage” which consists in replacing parts of the crossing roads from Bernstorffsgade to H.C. Andersensgade (him again!) by a green pedestrian area, which will connect the central station to the city hall square (Rådhuspladsen) and the main shopping street (Strøget). Even though this project contributes to the public spaces’ expansion and connectivity, it does not solve the debate on public vs. private exploitation of urban spaces.

Source : Google maps Satellite – Bispebjerg Bakke

source: Annabelle Moine, 10/09/2020 – Friksvarteret, Rostockgade 8, Copenhagen

A tactical urbanism in Copenhagen ?

Private space, citizen’s exploitation: what if courtyards were a starting point for a step-by-step conversion of green spaces? The Danish architect Lendager has come up with “UpGardens”, a project in Malmö (Sweden) which consists of semi-public green spaces. This project, in the perspective of tactical urbanism, aims to revitalize a former industrial neighborhood by installing vertical, shared vegetable gardens with the possibility of year-round gardening.

Tactical urbanism, or urban acupuncture, refers to a participative and temporary urbanism carried by citizens, communities and/or activists and which often resorts to art and events. In this perspective, delegating the management of courtyards to the public and above all to the citizens would contribute to making them responsible for maintaining and giving a new value to spaces that would now be shared.

Other major cities around the world are experiencing the spring of tactical urbanism initiatives: Paris (France), with ‘Les Grands Voisins’, a project aimed to accommodate refugees in a former hospital (led by the Aurore association since 2015), and Wichita (Kansas, USA), with the civil transformation of a car lane into a bicycle path by the 20/20/20 movement. These ‘urban guerilla’ and short-term projects are now giving rise to lasting transformations of urban space.

Source : Lendager Group, https://lendager.com/en/urbanism/up-gardens-en/

Open new gateways in both city and imagination

In comparison with other major cities like Paris and Wichita, the Danish capital city has got outstanding predispositions to meet its 2050’s goals. Its population is of moderate size (1.3 inhabitants in 2020), active and becoming younger – by 2031, demographic growth will be led by the working population and the ones below 18 years old. In this context, and considering the social trust among the Danes, these two unique characteristics are also two reasons to believe that Copenhagen, the UNESCO’ world capital of architecture for 2023, will give rise to a new imagination for tomorrow’s tales, far from the contrasts once portrayed by H.C. Andersen.

Annabelle Moine (LinkedIn)