Walking into the woods, an architect passes an anthill. He stops, intrigued. It looks like an inhabited mountain or a natural tower. It is swarming, crumbling and fixing itself. It seems to move and at the same time to be firmly grounded, like a cathedral of pine thorns that resists the breeze and defies gravity.

Verticality and height are symbols of wealth, boldness, fecundity in the occidental part of the world. In other parts of the world this represents human pride, inequalities, or the surveillance state. The city is even more fascinating for the one who overlooks it. But more than the monumental look, the functionality of a high-rise building – the way it relates to its surroundings and people – is key to ensure it is an integrated element in the urban composition.

While larger European metropoles like Paris, Marseille or London keep competing in building the highest towers, high rise architecture is not a common thing in Denmark. The architects and urbanists who are building the future Copenhagen’s skyline are facing a couple of social, cultural and geographical challenges – the highest point of Denmark peaks at 171m (Møllehøj).

Historically, the first high buildings were raised in Denmark in the early 20th century. But today, it does not seem to fit the traditional Danish architecture, which cares for harmony and frugality. Can towers become a positive element in the Danish landscape and contribute to the society’s well-being, which is so important for Danes? What can make a ‘good’ high rise architecture in Denmark ?

What does the high-rise architecture in Denmark tell us about how the Danish society works?

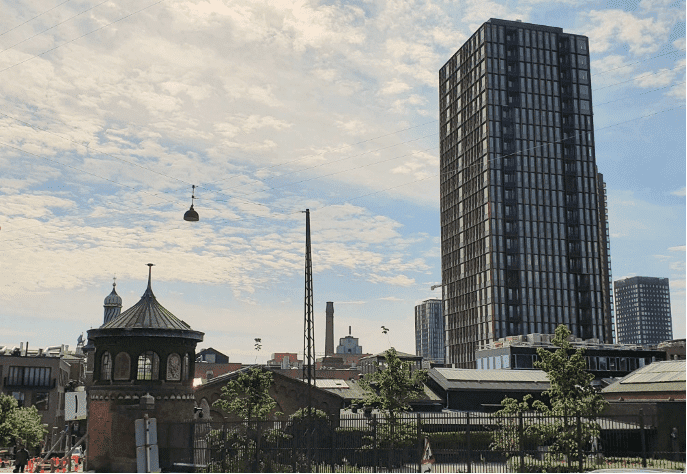

Carlsberg Campus, view from Søndermarken, Dahlerup Tower in the foreground, Pasteur Tower hidden behind it, Bohrs on the right from left to right (Source: Annabelle Moine)

At the turn of the 20th century, the Danish architecture grew significantly taller in order to establish the democratic power in Denmark. Radhustårnet, the city hall’s tower, was built in 1905 with inspiration from the Tuscan civil monuments. According to Martin Nyrop’s original plans, it was planned to be 89m high, 3m higher than Christiansborg’s spire, but the latter burnt down during a devastating fire in 1884. The citizens’ assembly (Borgerrepræsentationen), the highest political authority in Copenhagen, demanded that Radhustårnet was 105.6m high. Facing such strong a competition, Thorvald Jørgensen added three crowns to the rebuilt Christiansborg Spire, which finally reached 106.5m in 1932. After a period of great political instability, Radhustårnet and Christiansborg Palace contributed to the long-term establishment of a parliamentary system in 1901.

It has taken more than 90 years for a tower of this scale to be built: the 100-metre-high Bohrs Tower by architect Vilhelm Lauritzen was built in 2017. It is the first of nine towers that will form the future Carlsberg campus in the heart of Copenhagen. It will soon be followed by the Pasteur Tower (by the same architect), which should be 120m high.

Today, the construction of high-rise buildings is expected to foster urbanisation and social upgrade. They are likely to appear on former industrial sites for reconversion, such as the Carlsberg brewery site, which was active until 2008. This site, which has been inactive since 2008, is now a real historical legacy with its old warehouses, factories and chimneys, which renowned Danish architects have chosen to rebuild in what should become the future Copenhagen’s skyline, like the other great European cities have. Among them, Vilhelm Lauritzen, Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects, Cobe and Effekt – Together, they want to make it a vibrant multifunctional district, mixing new housing, offices and student campuses that should also address the great lack of affordable housing for Copenhageners – in theory. From an aesthetic point of view, all nine towers, which will be between 50 and 120m tall, should play elegantly with the color and materials’ palette of the old infrastructure.

Carlsberg Byen seen from the lakes (Source: Annabelle)

Bohrs, the first completed tower, is characterized by an optimized capture of daylight: the living-rooms are strategically located at the corners of the tower, where the windows are also the largest. The size of the side windows is reduced in order to limit heat loss and to refine the tower’s composition. Its brown ribbed aluminium skin, which is unfortunately lacking some depth and details, is at least aligned with the colors of the district.

People remain quite skeptical about Bohrs tower. It was even named one of Denmark’s ugliest buildings in a survey by the newspaper Berlinske in 2020. ‘ Why build the Pasteur Tower, an even taller tower, if all the flats in Bohrs are not sold yet? Jens Nyhuus, managing director of Carlsberg Byen’s, replied with sarcasm: ‘Danes have to learn how to live at this height’.

Ironic or serious criticism? This ironic statement sounds like Jules Verne’s uncle, who, during his visit to the Vor Frelsers Church (36m) in Copenhagen, said to his dizzy nephew: ‘Look,’ he said, ‘and look carefully! You must experience the vertigo.” (Journey to the Centre of the Earth).

It seems indeed that the towers are not really adapted to the Danish way of life. According to Jane Jacobs, the famous American urban planner and critic of the twentieth century, ‘the look of things and the way they work are inextricably bound together, and in no place more so than cities’ (The Death of Life of Great American cities). Food for thought.

Tour Nordbro à Nørrebro (Annabelle Moine)

The progressive assimilation of the Nordbro tower into Nørrebro neighbourhood gives hope to the builders of Carlsberg Byen. Norbro, a 100m high tower built in 2019 by Arkitema, remains quite isolated from other types of/examples of highrise architecture. Even though it is standing alone, the surrounding sport facilities and car parkings could realistically pave the way for other high buildings in the future as well. The depth of its metal facade recalls the notched mechanism of an old music box. An architecture of rhythm in a vibrant, multicultural neighborhood: the right tone is set. To make sure Nordbro becomes a real urban asset for the neighbors, it still requires to plan the surroundings’ in a way that suits Nørrebro’s people, instead of having people adapt to Norrebro’s new environment.

The future projects of Danish towers are looking as much disproportionate as uncertain: the 280m tower that Bjarke Ingels (BIG) suggested to build in Nordhavn, has been rejected. Karin Vestergård Madsen, Copenhagen’s mayor for technology and environment matters, gave a vague explanation: “We can certainly have a few tall towers when it makes sense, but we are not going to build tall towers just for the sake of height.” (Politiken). Is she referring snidely to the Radisson Hotel (Arne Jacobsen), a 61-metre-high cobblestone in the city center, or is she pointing out to at the Turning Torso (Santiago Calatrava), the only skyscraper of Malmo that is standing on the Danish horizon?

The future 3XN’s tower, the Lighthouse (Source: https://3xn.com/)

But delusions of grandeur still have a chance in the Danish province. A moins de 100 kilomètres de Aarhus, au village de Brande, le gratte-ciel proposé par Dorte Mandrup à la demande de ‘Monsieur Bestseller’, a obtenu le feu vert. The Danish billionaire, who owns the international retail clothing chain Bestseller, would have his own 320m high tower which will be visible from 60km away. The tower’s design is apparently inspired by Sauron’s tower in The Lord of the Rings. But no precise date for the start of the work has been set, according to Anders Krogh, the person in charge of the project. It is thus difficult to say whether the project will ever be completed.

In contrast on the harbor front of Aarhus, a 142m-high skyscraper from 3XN is under construction – the Lighthouse is to be completed in 2022 with the intention of “giving back to all, not only to those who live in the tower” (Rune Kilden, Developer, 3XN). This return – having urban life as close as possible to the water – relies above all on the development of the waterfront, including a promenade, a square and cafés.

If building high rise architecture remains a symbol of power and order, it has a different meaning up here. It means the city is coping with hardly affordable housing and urgent need for creating more of them, even though it usually creates more unaffordable housing. High-rise buildings also make the social inequalities visible to all, while the Danes promote both a flat architecture and social hierarchy. Side note: Denmark has a code of conduct that claims this fierce rejection of superiority: ‘Du skal ikke bilde dig ind, at du er bedre end os’. Don’t imagine you are better than us. (Jante’s Law, 1933).

Heights in the Danish fairy/fantasy

Fjordhusen, Olafur Eliasson (Sources : https://www.fjordenhus.dk/en/)

La tour maudite et la montagne hantée. Victor Hugo’s first novel, Han of Iceland (1823), describes a haunted mountain and cursed tower, both being havens for the vilest creatures of the story. The plot is set in the 1670’s in the Kingdom of Norway, whose capitol is Copenhagen. Two adventurers, a young nobleman and an old sage, are on their way to find and kill Han, the monstrous creature that lives in the remote mountains:

‘’On the gulf left shores, there is a wealth of runic stones, on which one can study the characters that gods and giants carved according to tradition. (…) It is in the tower of Vygla, which we are approaching, that the pagan king Vermund roasted St. Etheldera’s breast, our glorious martyr. He used wood from the true cross brought to Copenhagen by Ollaüs III and conquered by the Norwegian king. Attempts to make a chapel of this cursed tower have apparently been thwarted/in vain – all the crosses that have been placed there were successively consumed by the fire of heaven.’’ (Han of Island, Victor Hugo translation: Annabelle Moine)

This fantasy appears in some contemporary elements of Scandinavian architecture such as Fjordhusen, in the Vejle Fjord and Jutland region. This modern fortress hosts both offices and an exhibition space for the Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson’s artwork. Designed by the latter, Fjordhusen is a set of interlocking 28m-high-towers surrounded by the harbour’s waters. Between the towers, large openings reveal Eliasson’s artworks in glass. Inside, the atmosphere that grips the visitor is mysterious, welcoming and cold. The shadows undulate around the ambiguous angles, curves and rooms. The place is in constant dialogue with the sea, which submerges two rooms in the basement and is always visible from the dizzying windows. What a frightening workplace!

What if Danes just aren't great romantics?

Back in Copenhagen, it is clear that the contemporary Danish architecture is down-to-earth and realistic, like many of its people. Yet this does not prevent the city from being a field for dreams and entertainment.

Park n Play, Jaja Architects (Source: Nordic Insite https://www.nordic-insite.dk/en/essential-architecture-urbanism-copenhagen/ )

Think of Copenhagen as a huge playground. It has its candid atmosphere, thanks to its pure lines, ingenuous curves and naïve, uniform facades. It’s horizontal, layering the harbour landscape, extending on the canals and lakes. This ensures mobility and a harmonious articulation of the architecture with its urban plan. The winding bicycle bridges and the welcoming graveyards make the public space flexible and safe for all. In such an ergonomic city, height eventually seems superfluous.

The Forest Tower, Effekt architects (Photos et croquis: Annabelle Moine)

With one exception. Seventy kilometers from Copenhagen in the heart of Gisselfeld Klosters forest, EFFEKT studio’s spiral tower, built in 2019, shows the way to stand above the top of the trees. Reasonably high, simple and playful, it meets the Danish architectural standards. At (only) 45m high, it has been ingeniously built on a plateau 135m above sea level, giving the visitor reaching the top a majestic view of the island of Sjælland, without distorting the landscape. The EFFEKT tower is like a large hourglass set among and around the trees. The entire structure is made of corten steel, a raw material architects notably chose for its rusty color. This way the tower fits perfectly in its environment. Also it does not need to be painted every now and then like the Eiffel Tower.

To reach the top, there are no steps, just a ramp that turns and rises gradually. Another characteristic is its hourglass shape of the Forest Tower which gives a real cadence to its ascent: you go up faster and closer to the inner trees when the tower’s diameter narrows. As the diameter gets wider, the ascent slows down and the visitor is invited to observe the forest on the outskirt of the tower. Thus the panorama both inside and outside is constantly changing along the ascent. Each viewpoint on the way up is like a painting framed by the intersecting metallic beams, allowing the visitor’s imagination to run free. The tower simply offers a full experience of nature. Mission accomplished for the architect.

Of course, in Denmark there are no dormant volcanoes, no sea of clouds, no everlasting snow to believe you are in a Miyazaki animé or on the El Teide. The architect can’t reinvent the mountain in such a flat country. But it’s still much inspired by nature: the sea, the horizon, the forest. The tower becomes a positive element for the Danes when it fuels one’s imagination, for example when the depths of its facade play with light and shadow, or when it stands like a lighthouse to guide people either in the city or in the woods.

Likely in Denmark more than anywhere else, high-rise architecture only makes sense when it meets a need of the population. Here a tower is as much legit as is it functional, or even multi-functional in the context in which it stands. Indeed, height is less important than the Danish quest for ever greater social welfare – ‘samfundsind’.

Danish society therefore demands flexible and clever structures, which optimize the distance from home to work, groceries, public transportation, friends and nature. This concept of ‘micro-living’, which gives as much value to location as to housing design, is made possible by high-rise buildings. As an example for micro-living architecture, BIG is currently building the Kaktus Towers in Copenhagen, Kalvebod Brygge.

As an example for micro-living architecture, BIG is currently building the Kaktus Towers in Copenhagen, Kalvebod Brygge. Like The Lighthouse in Aarhus, it would not be surprising to see the next Copenhagen towers in Refshaleøen or Sydhavn. But Copenhagen and Aarhus, the two largest Danish cities, for now have the privilege of still being able to expand without densifying.

(Photo: Annabelle Moine. Kaktus towers: https://www.kaktus-towers.dk/micro-living)

Annabelle Moine (LinkedIn)